The

Sanftlebens

Silesian Roots:

It

appears that most Sanftlebens can trace

their origins back to an area in central Europe commonly referred to as

Silesia or Schlesien. In fact, it appears that many of the

Schlesien Sanftlebens (sometimes recorded as Senftlebens) were

concentrated in Nieder, or Lower, Schlesien, with quite a few in an

area south of the city of Breslau around the town of Frankenstein. It

appears that most Sanftlebens can trace

their origins back to an area in central Europe commonly referred to as

Silesia or Schlesien. In fact, it appears that many of the

Schlesien Sanftlebens (sometimes recorded as Senftlebens) were

concentrated in Nieder, or Lower, Schlesien, with quite a few in an

area south of the city of Breslau around the town of Frankenstein.

Although Slavik peoples began to settle in Silesia under the feudal

sovereignty of Bohemian dukes as early as the 9th century, the region

did not come under the rule of a Polish King until the 10th

century. As the area was sparsely populated, the Bohemian

rulers actively recruited Germans to settle in the area, and by the

mid-1200s the region, to include its towns

and cities, was distinctly Germanic. In the mid-14th century,

Poland renounced all claim to the region, the King of Bohemia

assumed sovereignty, and Silesia became part of the Holy Roman Empire

and subsequently the Austrian Empire from 1526 until 1742 when it was

annexed by Prussia.

In the closing months of World War II, the Soviet Army began to

systematically drive the German inhabitants of Silesia from their

homes, forcing them to walk westward through the snow in temperatures

that approached -15 degrees Fahrenheit. Frequently the long,

slow-moving columns were strafed by Soviet aircraft, and records of

outright murder by Soviet ground forces exist. It has been

estimated that over 2 million Germans died from starvation, cold, and

Soviet bullets during this ethnic cleansing . Following the

war, Schlesien

was ceded

to Poland and renamed Slask; Breslau was renamed Wroclaw; and

Frankenstein was renamed Zabkowice Slaskie.

In many ways, the ravages of Silesia's ethnic cleansing during the 20th

century is reminiscent of the

horrors

inflicted on the region during

the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). During the early years of

the

Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, the majority of the

population of Bohemia and Silesia became Lutheran. In 1617,

Ferdinand, the Catholic Duke of Styria, became the King of Bohemia and

immediately ordered the Protestants of Prague to cease building

churches. The Protestant

princes

resisted as

they believed this act to be in violation of rights of religious

freedom

granted to them by the throne nearly ten years earlier. Two

of

Ferdinand's ministers who tried to enforce the edict were tried at an

assembly in Prague Castle, and when found guilty, physically thrown

through the highest windows of the Bohemian Chancellery.

Fortunately for the ministers, they survived the fall, but only because

they had landed in a giant manure pile. This "Defenestration

of

Prague" sparked the Thirty Years War. Protestant

princes

resisted as

they believed this act to be in violation of rights of religious

freedom

granted to them by the throne nearly ten years earlier. Two

of

Ferdinand's ministers who tried to enforce the edict were tried at an

assembly in Prague Castle, and when found guilty, physically thrown

through the highest windows of the Bohemian Chancellery.

Fortunately for the ministers, they survived the fall, but only because

they had landed in a giant manure pile. This "Defenestration

of

Prague" sparked the Thirty Years War.

In 1929, Heinrich Gabriel authored a book, Am Born der Heimat,

that included a

memoir of life in Silesia during the Thirty Years War, written by the

city clerk of Frankenstein, Kaspar Gloger. His father, a

master

baker, had served as a city-juror from 1635-1640 and a councilman from

1640 until his death in 1650.

Children, when I tell you my

experiences in

the Thirty Years

War, terrifying pictures appear in my soul.

Still

today after twelve years of the peace, I am

sometimes frightened

in my sleep if I dream of Saxon Landsknechts and Swedish cavalrymen.

In the first two years of the

war, I knew

little about it as

I was only six years old. Also,

those

of us living in Schlesien cared little about the  troubles

that the Emperor [Ferdinand II] had

begun in Bohemia. But

21 February 1620

is a date that I still remember well.

We

children followed a group of magnificent coaches

that had appeared at

the arboretum as it traveled to our castle. troubles

that the Emperor [Ferdinand II] had

begun in Bohemia. But

21 February 1620

is a date that I still remember well.

We

children followed a group of magnificent coaches

that had appeared at

the arboretum as it traveled to our castle.

In the third car sat the

newly selected King

of Bohemia,

Friedrich V, who was stopping for the evening on a trip to Breslau to

receive

homage. When I returned home late that evening, my father scolded me

and made

me stand alone in the room as a lesson because my curiosity at the

castle may

have led others to believe that I was celebrating the Bohemian

insurrection that followed the death of the Holy Roman Emperor,

Matthias, in 1619 and his succession by

Ferdinand II. (During

1617, Matthias

reversed a long-standing policy of state tolerance of the Protestants

and

attempted to forcefully reconvert them to the Catholic faith. After his

sudden

death, Ferdinand began to increase the pressure, and the mobility of

Bohemia

revolted.) Despite

my father’s sympathy

for the Protestant cause, he worried that the conflict would soon

spread to

Schlesien and devastate our homeland. His fears were correct for

following the defeat of

the Bohemians at the Battle of White Mountain (where their army of 25,000 was overwhelmed

by the

superior numbers of the Imperial forces)

Schlesien

overflowed with

deserters, wounded, and refugees.

Battle of White Mountain (where their army of 25,000 was overwhelmed

by the

superior numbers of the Imperial forces)

Schlesien

overflowed with

deserters, wounded, and refugees.

Still, we might have been

spared from the

conflict as most of

the Protestant Schlesichen nobility quickly withdrew its support for

Friedrich,

however in 1621, the Lutheran Duke Johann George von Jaegerndorf, led

his

forces from Brandenburg to confront the Imperial Army at fortified city

of

Glatz. Now,

the war came; the

Imperial

forces retreated from Glatz and burned the fields of Camenz and

Giersdorf as it

departed. Later in

August, the Imperial

Army returned and occupied Saxony and Schlesien as it laid siege to

Glatz.

Oh,

children, the soldiers were upon us! The scum of the earth. They cared nothing for our

region or

traditions. They

plundered our homes

and farms, and if we resisted we were

assaulted and

murdered. Our

choice was between misery or

grisly

death. The Imperial

army occupied our

homes for 42 weeks without ever attacking

the Protestant

forces at Glatz. Frankenstein

alone was

required to support

1500 soldiers. It

was worse for the

nearby villages of Kunzendorf, Baitzen, and Altman, which were

completely

burned for their Protestant support.

Finally,

on 3 June 1622, the Imperial forces brought

in two large

cannons, named the Wingless Dragon and the Black Sow to fire upon the

walls of

Glatz, however the city continued to resist until 25 October.

occupied our

homes for 42 weeks without ever attacking

the Protestant

forces at Glatz. Frankenstein

alone was

required to support

1500 soldiers. It

was worse for the

nearby villages of Kunzendorf, Baitzen, and Altman, which were

completely

burned for their Protestant support.

Finally,

on 3 June 1622, the Imperial forces brought

in two large

cannons, named the Wingless Dragon and the Black Sow to fire upon the

walls of

Glatz, however the city continued to resist until 25 October.

After

Glatz was retaken, the Imperial army gradually left the area, however

we now lived with poverty, hunger, and inflation.

Little

food was available in Frankenstein as all of our farms had

been destroyed. Work

and trade came to

a halt. Despite the

inability to earn a

living, we were required to pay the Empire one silver reichstaler and

15 to 20

ordinary talers each year. For

these

reasons, despite the peace, the city and surrounding farms could not

recover.

In August, the Empire

declared a new war

emergency, and the

Imperial army  conscripted

one-tenth of all

Schlesien men to serve unwillingly

in its labor battalions. Protestent

forces returned to our region as did Wallenstein’s Imperial army. The demands on our food

supply were

exorbitant. We

requested that

Wallenstein by-pass our city, which he did but only after demanding we

supply

beer, wine, and bread for 15,000 men.

I

spent long days and nights with my father in his bakery, but that was

far

better than having the Wallensteiners here in Frankenstein. Then, despite his promise,

Wallenstein

garrisoned

an infantry regiment in our city the following January. For six months

it

stayed making unreasonably severe demands for food and money. We were forced to give

them all of the

latter, and could only suffer their brutality in silence. To avoid the misery, my

sister, Annemarie,

and our father moved from town to Reichenstein to stay with my Uncle

Ziegler. My

brother, Christoph, and I

stayed, for we knew how to avoid the soldiers. conscripted

one-tenth of all

Schlesien men to serve unwillingly

in its labor battalions. Protestent

forces returned to our region as did Wallenstein’s Imperial army. The demands on our food

supply were

exorbitant. We

requested that

Wallenstein by-pass our city, which he did but only after demanding we

supply

beer, wine, and bread for 15,000 men.

I

spent long days and nights with my father in his bakery, but that was

far

better than having the Wallensteiners here in Frankenstein. Then, despite his promise,

Wallenstein

garrisoned

an infantry regiment in our city the following January. For six months

it

stayed making unreasonably severe demands for food and money. We were forced to give

them all of the

latter, and could only suffer their brutality in silence. To avoid the misery, my

sister, Annemarie,

and our father moved from town to Reichenstein to stay with my Uncle

Ziegler. My

brother, Christoph, and I

stayed, for we knew how to avoid the soldiers.

Wallenstein and his army

finally left in

June, but before

we could catch our breath, as Schlesien was now entirely under Imperial

domination, regional Catholic forces arrived and garrisoned our area

for 26

weeks behaving nearly as badly as the Imperial troops.

On top of all of our troubles, the Empire

forbid us to hold Lutheran services as we had been doing in the city

for sixty

years, and beginning in 1629 we were forced to become Catholic.

For the

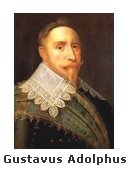

next three years, there was peace in

Frankenstein, but in 1630, the

Swedish King Gustavus Adolfus deployed his forces to assist our

Protestant

princes. Within two

years, the Swedish

troops arrived in Schlesien and forced the Imperial Army to withdraw

from

Breslau. In their

retreat, they

temporarily

occupied Frankenstein. Upon

leaving on

3 June 1632, they outrageously started a fire at the northwest corner

of the

ring that almost destroyed the entire city.

Only

the parish church, the school, and ten houses

survived. We

survived too, but only with

our naked

lives. The Swedes

arrived in September,

and everyone once more became Lutheran, however in November the

Imperial army

returned in force and bombarded the city.

The

Swedish forces withdrew, and we were forced to

change our faith once

more. For the

next three years, there was peace in

Frankenstein, but in 1630, the

Swedish King Gustavus Adolfus deployed his forces to assist our

Protestant

princes. Within two

years, the Swedish

troops arrived in Schlesien and forced the Imperial Army to withdraw

from

Breslau. In their

retreat, they

temporarily

occupied Frankenstein. Upon

leaving on

3 June 1632, they outrageously started a fire at the northwest corner

of the

ring that almost destroyed the entire city.

Only

the parish church, the school, and ten houses

survived. We

survived too, but only with

our naked

lives. The Swedes

arrived in September,

and everyone once more became Lutheran, however in November the

Imperial army

returned in force and bombarded the city.

The

Swedish forces withdrew, and we were forced to

change our faith once

more.

Our city now was little more

than a heap of

debris, and it

again had to grant Wallenstein’s armies passage.

The

outlying villages were in even worse shape.

The Imperial army brought us another dark

guest too, “the black plague.” I

knew

from my grandfather that the plague had visited Frankenstein three

times in the

past; that was in 1521, 1568, and 1606. Now it

came again and took thousands in our

principality. Large

numbers began dying in

the city in August

1633, and it continued until January.

I

alone carried around 30 corpses to the cemetery.

My

dear mother, brother Christoph, and the good Annemarie died

rapidly one behind the other. The

Imperial army flooded the quiet city, plundering all that remained, and

destroying the villages of Quickendorf, Peterwitz, Kleutsch, and

Zuelzendorf by

fire. Those who

could, fled to the

forests to escape the atrocities.

For

one and a half years, the scourge of God was upon us, yet we bore it

all as

routine. Even the

Prager Partial Peace

of 30 May 1635, which included Schlesien and freed us from supporting

Imperial

troops, brought no joy.

and 1606. Now it

came again and took thousands in our

principality. Large

numbers began dying in

the city in August

1633, and it continued until January.

I

alone carried around 30 corpses to the cemetery.

My

dear mother, brother Christoph, and the good Annemarie died

rapidly one behind the other. The

Imperial army flooded the quiet city, plundering all that remained, and

destroying the villages of Quickendorf, Peterwitz, Kleutsch, and

Zuelzendorf by

fire. Those who

could, fled to the

forests to escape the atrocities.

For

one and a half years, the scourge of God was upon us, yet we bore it

all as

routine. Even the

Prager Partial Peace

of 30 May 1635, which included Schlesien and freed us from supporting

Imperial

troops, brought no joy.

The following three years

were calmer, and

much of the city

could have been rebuilt using timber from the surrounding forests, but

Frankenstein now had only about one-sixth of its pre-war population,

and their

desire to build was paralyzed by fear of renewed hostilities. My father, however, was

one of the few with

energy, resolution, and faith in God despite all of the past strokes of

fate

and he heartily began to rebuild his bakery.

Fighting,

however, resumed in

1639 and continued until the final conclusion of the war.

Our lot was with the Swedes,

oppressors

though they could

be, and they occupied our city three more times: 1639, 1642, and 1645. The whole time, the

Imperial army harassed

us and sucked our livelihood like leeches with tax collecting stations

and toll

roads. With the

back and forth of troop

movements, we hardly knew which armies we were forced to accommodate

in our

city; we found them all to be thieves, robbers, murderers, and

arsonists. The

soldiers, themselves, were

no longer

concerned with fighting and victory; they had become gangs of robbers

and

highwaymen, staying only where there were things to be stolen or

consumed.

I wish to also tell of the

last great battle

for possession

of our castle. By

1645 our life was so

hard

under the Imperial gang that occupied our city, that we actually wished

we were

part of Sweden. Then,

they finally came

on 1 October under the leadership of General Koenigsmark.

Despite our agreement with

the general and

our delivery of

bread and beverage for 8,000 soldiers, no house remained unplundered. The next day the Swedes

advanced to

Patschkau without occupying the castle.

However,

they returned on 27 October and fortified

the city with a

strong unit and several cannons. The

Swedish leader, Captain Kraegel, clearly intended to stay, as he

resurrected

Lutheran services in the city and established defenses in the castle. Approaches

to the castle were  cleared

and

defensive barriers and trenches were

prepared. The city

was required to provide the Swedes

with

food, cattle, and

grain. cleared

and

defensive barriers and trenches were

prepared. The city

was required to provide the Swedes

with

food, cattle, and

grain.

The Imperial attacks were not

long in coming,

however they

were weak for the first six months, as the only damage inflicted was to

terrorize the citizens. Then

a large

Imperial army under the command of General Montecuccoli appeared

between the

end of June and 1 July of 1646 and attempted to force the Swedes out of

the

region. Since Kaegel could not hold the entire city against such

overpowering

odds, he and his soldiers withdrew to the castle to make a last stand. The Imperial army began

bombarding the

castle on 2 July with three heavy cannon placed on the Zadler Church

Bridge and

two mortars on Guergaes lane. Infantrymen

fired from trenches, barricades, and

windows, and repeatedly

assaulted the castle at night. The

Swedes courageously defended the castle for two weeks until mines were

emplaced

under the castle walls. They

surrendered on 13 July, and we became part of the Empire once more.

Count Montecuccoli then

ordered the castle to

be destroyed

so that the Protestants could never again use it as a fort. A sea of flame devastated

its insides and

left only the walls standing. The

powerful gate tower, however, resisted even a ton of powder.

We thought surely after this

destruction of

the castle that

the battles would now pass us by; however for the next two years,

Imperial

troops continued to move through our principality, extorting funds,

stealing

cattle and grain, and keeping us a shantytown.

Finally,

the war

ended with the Peace of Westphalia on 4

October 1648, but life improved only gradually, and we continued our

suffering

for many more years. Even today as I

write in 1660, the horrible wounds of the war still hurt. But

everywhere, new life is now beginning:

the farmer again plows his field; the businessman fills his warehouse,

and the

craftsman toils in his workshop. All

are anxious and hopeful.

Although

Herr Gloger

does not address it in his memoir, following the Peace of Westphalia,

Silesians were "strongly" encouraged to rejoin the Catholic faith, and

most did. Many of those families that did not, eventually

moved

to Protestant areas.

Whether or

not young

Christoffer Sanftleben lived in Frankenstein, this is the Silesian

climate he would have entered upon his birth in 1646. While

only

family records attest to his birth, and no records document his early

life, what is known is that Christoffer eventually became a cavalryman

in the Swedish Army.

To Christoffer

Sanftleben

|